China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, officially launched its National Emissions Trading System (ETS) in 2021. This is the largest ETS globally, with long-term goals to reduce emissions through market mechanisms while ensuring economic growth. However, China’s ETS has distinct characteristics compared to similar systems, such as the European Union ETS (EU ETS). The development journey of China’s ETS not only provides valuable lessons but also opens opportunities for Vietnam to engage in and develop similar mechanisms.

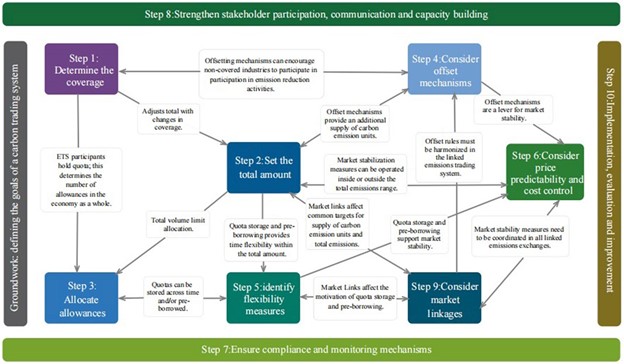

10 steps of developing ETS. Source: Effects of enterprise carbon trading mechanism design on willingness to participate—Evidence from China

Local ETS pilots

China’s national ETS, established in 2021, was built upon the practical implementation and experimentation of local ETS programs. Between 2013 and 2016, China developed regional ETS systems in major provinces and cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenzhen, Chongqing, Hubei, and Guangdong. These local mechanisms targeted various sectors such as energy, steel, cement, and aviation.

These systems played a critical role in testing mechanisms and gathering experience for the national system. The national ETS and local ETS programs have a complementary relationship, shaping China’s greenhouse gas emission reduction strategies. Carbon credits from local ETS programs, such as China Certified Emission Reductions (CCER), Forest Carbon Emission Reductions (FCER), and Fujian Forestry Certified Emission Reductions (FFCER), are accepted for compliance in the national ETS.

Innovation and ownership in renewable energy

China’s strategy for developing low-emission energy tied to domestic capacity-building began in the early 2000s. A key milestone was the introduction of the Renewable Energy Law, enacted by the Chinese National People’s Congress on January 1, 2006. This law classified renewable energy as wind, solar, hydro, biomass, and geothermal power. A dedicated fund was established to support renewable technology development, offering VAT exemptions to developers. Operators of wind farms could claim carbon reduction credits sold internationally under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) framework.

The policy of “indigenous innovation” (Zizhu Chuangxin, 自主创新) was formalized in November 2009 with the issuance of Circular 618, which certified National Indigenous Innovation Products. This directive focused on six high-tech sectors, including new energy, offering government procurement incentives, provided intellectual property ownership remained with Chinese companies.

During the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010), the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) set ambitious renewable energy targets: 190 GW of hydropower, 10 GW of wind, 3.3 GW of biomass, and 0.3 GW of solar energy. These targets were expanded at the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Conference to 200 GW of wind and 30 GW of solar by 2020. By the end of 2023, China had achieved a total renewable energy capacity of 1,260 GW, comprising 440 GW of wind and 610 GW of solar, accounting for 43% of the nation’s 2,920 GW total energy system capacity.

Development of international markets

China’s renewable energy industry has achieved international success, extending its reach to the United States. In September 2011, Goldwind, a Chinese company, installed China’s first three wind turbines (4.5 MW) in Minnesota, USA. That same year, China’s exports of solar panels and modules to the US doubled, reaching $2.6 billion, accounting for approximately 42% of the US market and exceeding US solar exports to China by over 30 times. These exports are part of China’s significant efforts to develop low-carbon energy sources domestically and abroad.

As China’s industries in wind power, solar energy, electric vehicles, “clean coal,” and nuclear power expand, its high-value exports and investments in global low-carbon energy sectors are also expected to grow.

Status of China’s ETS

Although China’s ETS is still in its early stages, it is already the world’s largest by emissions volume. Currently, the national ETS includes only the power sector (electricity and heat), responsible for emitting 5 Gt of CO₂ annually, which accounts for 15% of global emissions and 40% of China’s total emissions.

However, in the past four years, China’s ETS has struggled to effectively reduce emissions. Compared to its European and American counterparts, China’s ETS allocates too many free credits, leading to low trading prices (ranging from $7–$8 per ton in China compared to $58 per ton in the EU ETS). Low prices limit financial incentives for companies to adopt strong emission-reduction measures.

Domestic and International Impact

- Domestic Challenges: The lack of sectoral diversity in the ETS restricts its ability to drive significant emissions reductions across the entire economy. To address this, China plans to expand its ETS to include the steel, cement, and aluminum industries.

- International Engagement: China has not yet participated in ITMO markets, nor has it implemented corresponding adjustment (CA) mechanisms for international transactions. Expanding into ITMO could enhance transparency and elevate the global credibility of its carbon credits.

Lessons for developing an ETS

China’s ETS, while making significant progress, remains a work in progress. It provides valuable lessons on building a carbon credit market within complex economic and political contexts. Vietnam, with its strong commitment to emissions reduction, can leverage these experiences to develop an effective ETS tailored to national conditions.

- Strong Legal and Policy Framework: China established a robust legal and policy framework, with the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) (now the Ministry of Ecology and Environment – MEE) overseeing the national ETS. This ensured cohesion and efficiency in implementation. Vietnam needs a clear legal framework, clearly defining regulatory authorities and detailed guidelines to coordinate ETS operations effectively.

- Pilot Programs Before National Implementation: China began with regional ETS pilots to gather insights before rolling out the national ETS in 2021. Vietnam could similarly initiate pilot projects in specific regions or sectors (e.g., energy or transportation) to test and optimize the system before scaling up. For example, Ho Chi Minh City could leverage Resolution 98 of the National Assembly to implement a pilot ETS.

- International Transactions and ITMO Engagement: China has not yet participated in ITMO transactions or implemented tools like Corresponding Adjustments (CA). Vietnam can draw from this and focus on international market engagement to attract capital from developed nations. By incorporating CA tools, Vietnam can enhance transparency and build trust in its carbon credits.

Stay tuned for the next part, where we explore how Thailand leveraged ITMO credits for transactions with Switzerland.

Bùi Huy Bình, Director of TraceVerified Climai, an AI Project in Global Carbon Credit Transaction Consulting.

Source: The Saigon Times, Issue 51-2024, published on December 19, 2024.